ReDot Fine Art Gallery stands as a conduit for Indigenous Australian voices, advancing a mission rooted in respect, preservation, and exchange. By working exclusively with Aboriginal-owned and governed art centres, the gallery ensures ethical sourcing that directly uplifts communities and sustains cultural law. Each work presented is not only an artwork, but an act of empowerment, affirming self-determination and contributing to community development through practice.

With a curatorial approach that prioritizes both depth and diversity, ReDot fosters a nuanced appreciation of Indigenous cultural expression, offering audiences comprehensive context alongside visual encounter. In doing so, the gallery bridges ancient traditions with contemporary appreciation, positioning itself as a definitive platform for Indigenous art in Singapore and across the Asia-Pacific, while connecting these resonant forms to a global audience.

We sit down with Giorgio Pilla, owner of the ReDot Fine Art Gallery to discuss his journey from finance to art, the ethics of representing Indigenous artists, and the evolving role of the art gallery in the digital age.

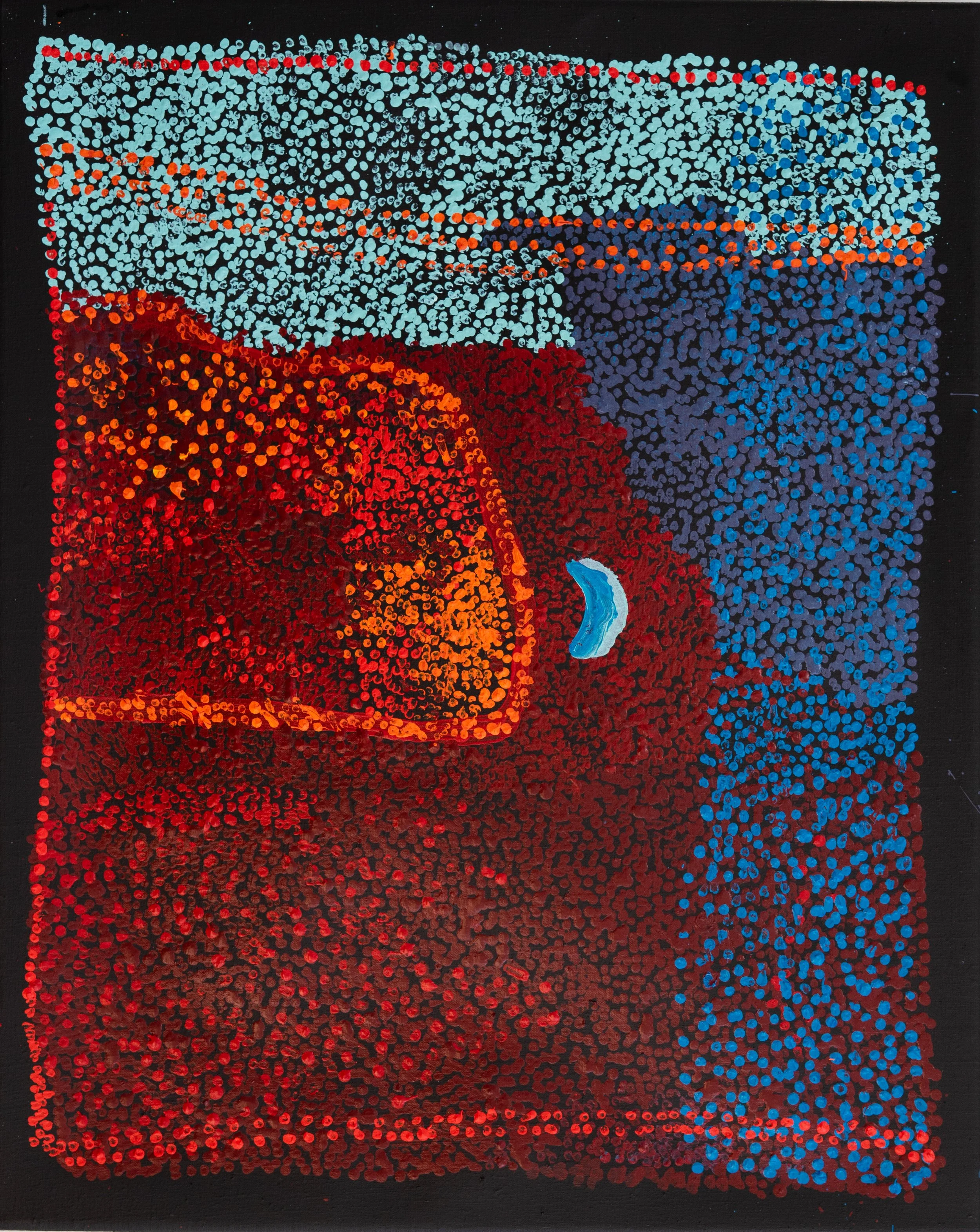

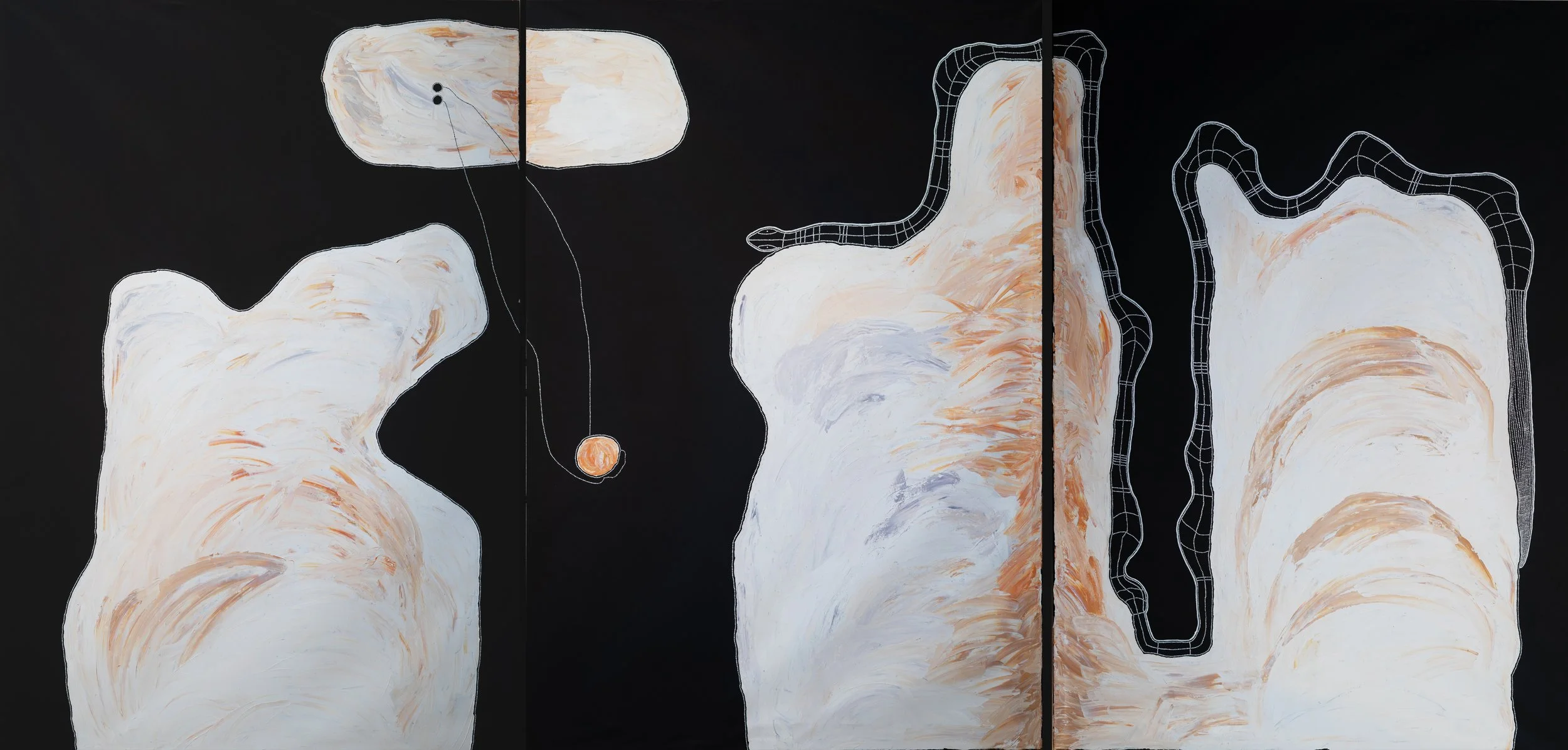

American Express Centurion Dinner Install Image

From investment banking to Indigenous art dealing is a rare leap. What was the moment that truly catalyzed that shift for you?

GP— The leap from investment banking to dealing in Indigenous art might seem unusual, but for me, it wasn't a sudden break; it was a gradual pull, culminating in a definitive moment of realization. My initial exposure to Indigenous Aboriginal art during banking trips to Australia sparked an initial curiosity which then became a deep interest, but the true catalyst for the career shift came down to a profound sense of purpose and authenticity that I felt my finance career could no longer satisfy after a career that had spanned almost 15 years.

The investment banking world, while intellectually stimulating and financially rewarding, eventually felt like it had run its course for me, and whilst it remains a huge part of my essence and I remain extremely proud of it, a more tangible connection to human experience and cultural value was calling me. Deals were becoming more abstract; success started to feel that it was increasingly being measured purely in numbers. The satisfaction, though real, was becoming more fleeting. It became increasingly evident that I needed a career pivot.

In contrast, the more I learned about Indigenous Australian art, the more I understood its immense cultural depth. It wasn't just beautiful; it was a living, breathing testament to millennia of history, spirituality, and connection to land. I saw how this art empowered communities, preserved stories, and offered a unique bridge between ancient traditions and the "new" contemporary world. The specific "moment" that truly crystallized this shift wasn't a single dramatic event, but rather a culmination of many experiences that built upon each other. It was the quiet privilege of meeting artists in remote communities at their art centers. Witnessing their dedication, the profound connection they had to their work, and how "the art" directly supported their families and cultural practices, which was incredibly powerful. These interactions contrasted sharply with the sometimes-impersonal nature of high finance. It was also the realization that I could use my skills, honed over many years in a demanding fast-moving environment, to advocate for something truly meaningful that held great appeal.

I saw a unique opportunity to build a bridge between these incredible cultural treasures and a vast global audience, ensuring ethical practices and fair returns for the artists. The idea of helping to elevate these voices on an international stage, while adhering to the highest ethical standards, became an irresistible draw. The choice, ultimately, became clear: to pursue a path where my work could contribute not just to economic value, but to profound cultural understanding and the preservation of an ancient legacy. It was a shift from dealing with abstract financial instruments to engaging with tangible expressions of human spirit and heritage. This quest for deeper purpose and authenticity was the true catalyst for my pivot into the world of Australian Indigenous art.

You've mentioned that your discovery of Aboriginal art came through visits to galleries during your banking trips to Australia. What was it about those works, especially the abstract minimalism, that first interested you?

GP— My fascination with Aboriginal Indigenous art, particularly its abstract minimalism, truly began during those early banking trips to Australia in the early 1990s. Initially, it was a striking visual encounter that attracted me, but very quickly, it evolved into something much deeper. Here's what initially captivated me:

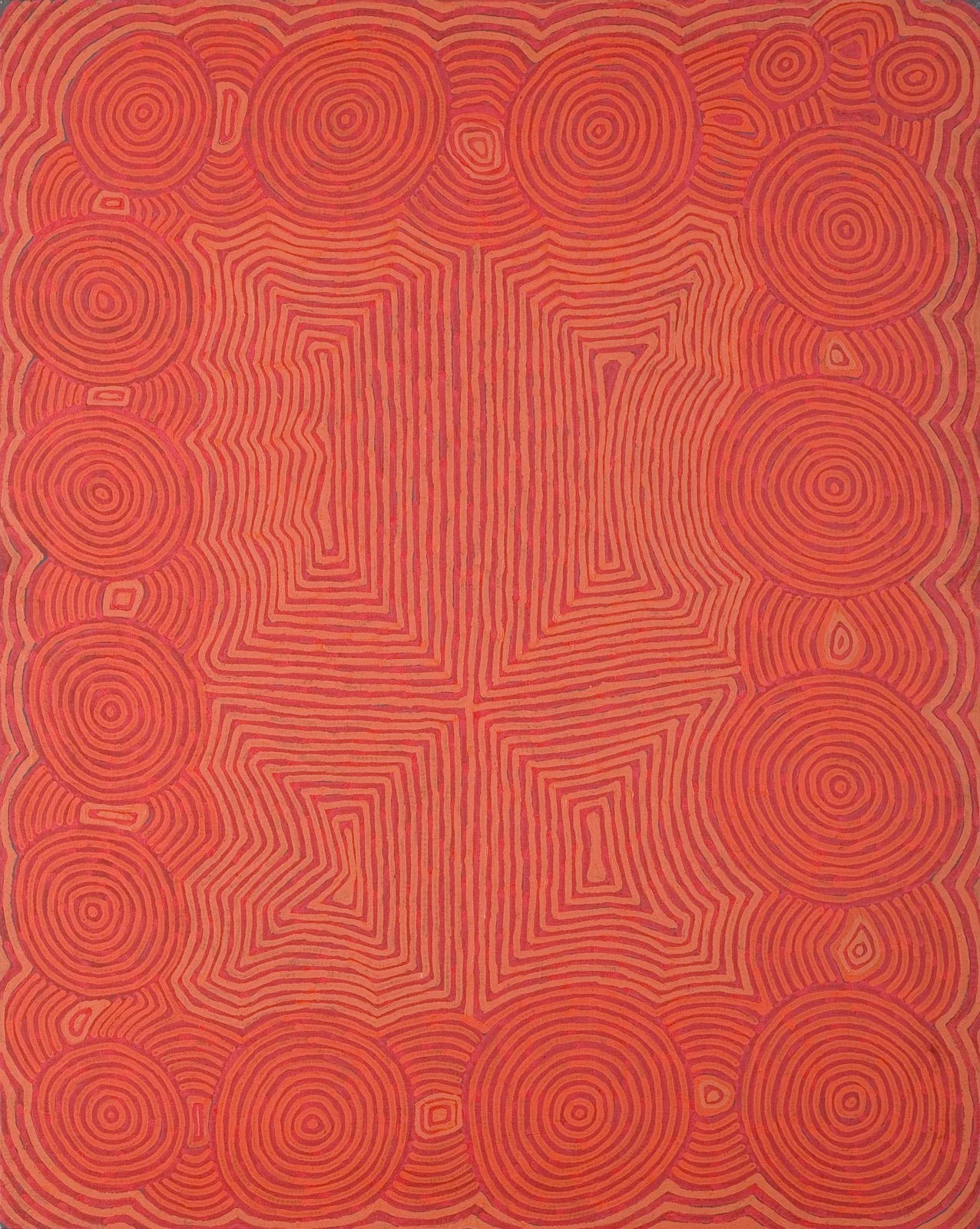

The Immediate Visual Impact: Hypnotic Repetition and Rhythm - Artists such as George Tjungurrayi and Ronnie Tjampitjinpa's monochromatic, parallel lines or concentric circles. This repetition creates a powerful optical vibration and a sense of endless movement. It's not static; it pulsates and draws your eye across the surface in a mesmerizing way. It appealed to my eye. Despite their complexity, the designs often boiled down to fundamental geometric forms. This simplicity was incredibly elegant and powerful. It wasn't cluttered; it was distilled essence.

Coming from a background exposed to Western art history, my mind immediately drew parallels to movements like Op Art (Victor Vasarely, Bridget Riley) or even Minimalist art. The clean lines, the exploration of perception, and the reduction of forms felt familiar on a purely aesthetic level. However, it quickly became clear that this wasn't just "Op Art from the desert." The power wasn't just in the visual trickery; it was in the meaning. This art was not merely abstract for abstraction's sake. It was a visual language deeply rooted in millennia of cultural and spiritual knowledge. This layered meaning elevated it far beyond purely formal experimentation.

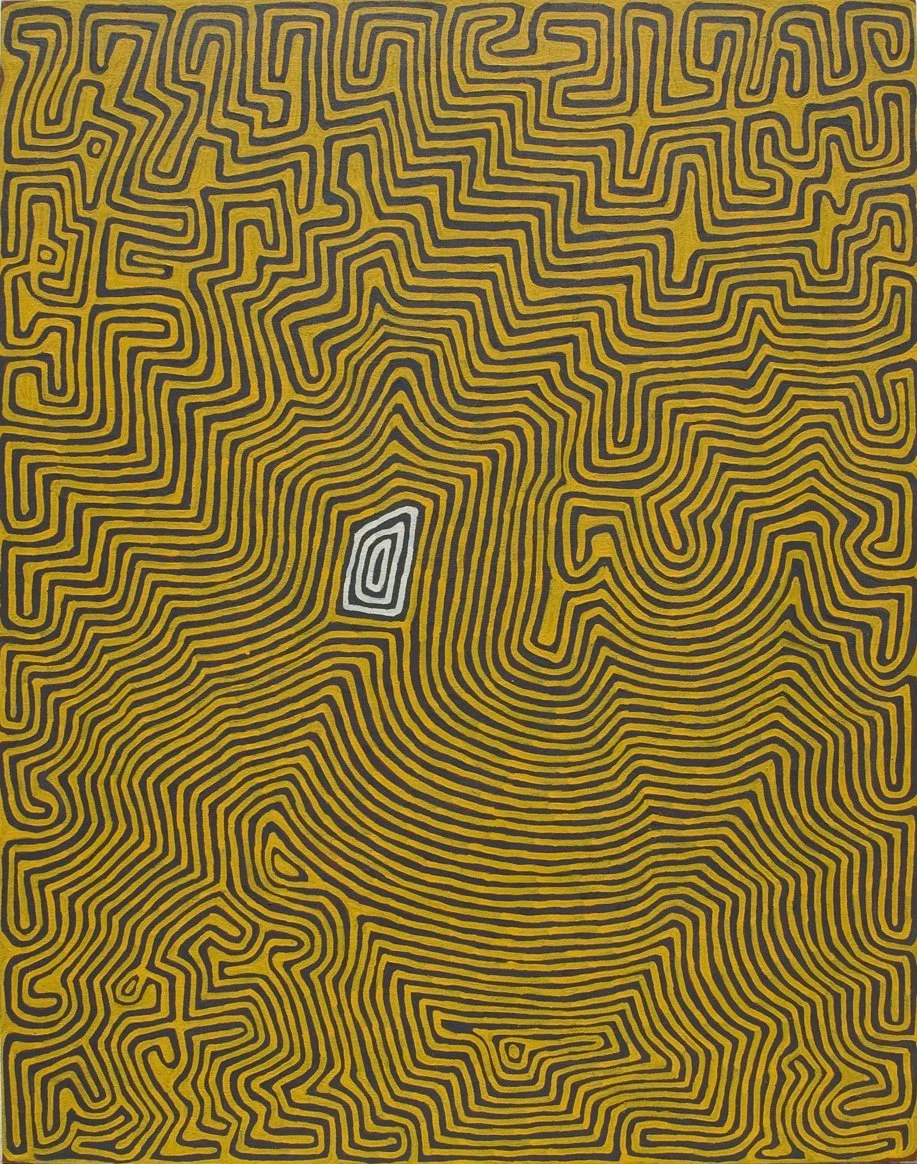

Learning that these seemingly abstract patterns were in fact highly sophisticated "maps" of ancestral lands, representations of dreamtime stories, and embodiments of sacred law was profoundly moving. It transformed the art from beautiful patterns into living, breathing narratives. The idea that lines could represent ancestral journeys, waterholes, sandhills, or even the subtle undulations of the landscape, imbued the "minimalism" with an incredible depth and gravitas. It was a tangible link to one of the world's oldest continuous cultures.

It represented a completely unique approach to art that I hadn't encountered with such power before. It wasn't about figuration in the Western sense, nor was it purely symbolic in a way I could immediately decode. It demanded a different kind of engagement - one that encouraged learning and respect for its originating culture. The "less is more" aspect of "minimalism," in this context, amplified the spiritual and cultural weight rather than diminishing it. Every line, every dot, had purpose and belonged to a grander narrative.

In essence, what first interested me was the powerful aesthetic, its surprising resonance with Western art, yet complete isolation from it, and the immediate curiosity it sparked about the profound cultural meaning embedded within every dot and stroke. It was a revelation that art could be so visually compelling while simultaneously being a direct conduit to ancient wisdom and an enduring connection to country. It fundamentally reshaped my understanding of what art could be.

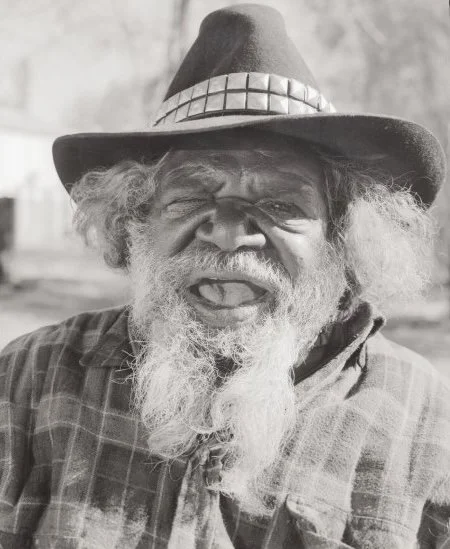

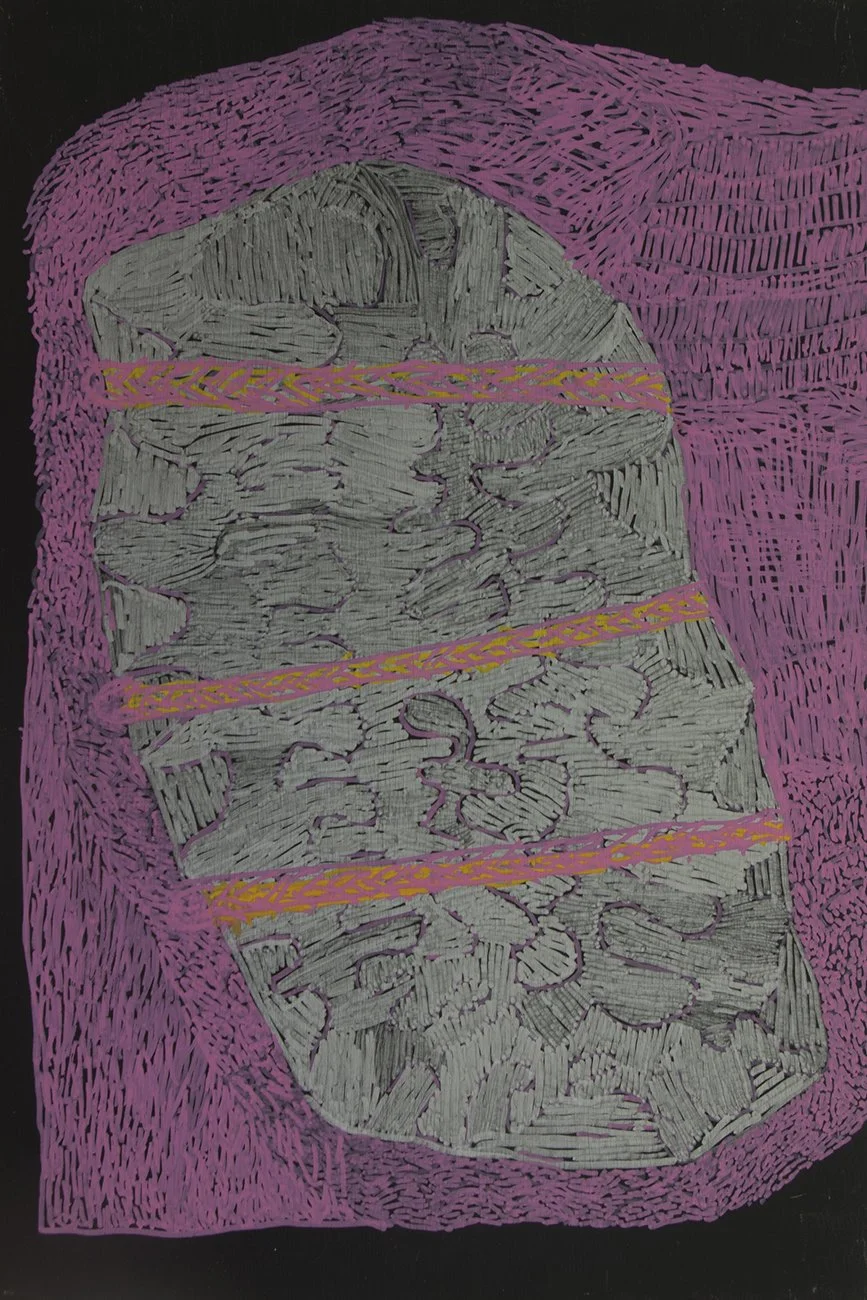

Artist Patju Presley

ReDot Gallery has carved out a very distinct niche representing Australian Indigenous artists. Can you speak to the ethical guardrails you've put in place when working with Indigenous artists and what does responsible representation look like in your gallery practice?

GP— At ReDot Fine Art Gallery, our ethical guardrails are built on a foundation of respect, transparency, and genuine partnership with Indigenous artists and their communities.

Here are the core principles we adhere to:

a) Direct Sourcing from Ethical Art Centres: This is paramount. We primarily source our artworks directly from Aboriginal-owned and governed art centres as the first point of sale. Increasingly we also source in "ethical" secondary marketplaces (clients and auction houses).

These art centres are vital community-based organizations that ensure:

i. Fair Payment: Artists are paid fairly and promptly, with prices set by the artists or the centres themselves.

ii. Artist Control: Artists maintain intellectual property rights over their designs and stories.

iii. Community Benefit: Sales directly benefit the artists and, more widely, their communities, funding essential services and programs.

iv. Cultural Governance: Art centres are run (or guided) by Indigenous people, ensuring cultural protocols are respected.

b) Provenance and Authenticity: Every artwork we acquire and sell comes with impeccable provenance. This means a clear, verifiable history of the artwork's origin, artist, and journey from the art centres to our gallery or end client. We provide certificates of authenticity issued by the art centres, guaranteeing the artwork's genuine Indigenous creation and ethical sourcing.

c) No Speculative Deals or Exploitation: We explicitly avoid "carpetbagging" or engaging with unethical dealers who exploit artists directly, often in remote communities, paying low prices and bypassing art centre structures. Our relationships are long-term, built on trust and mutual respect, not opportunistic "short term" gain.

Responsible representation for ReDot Fine Art Gallery isn't just a policy; it's ingrained in our daily operations and our fundamental ethos. It's about ensuring that the incredible artistic talent and cultural depth of Australian Indigenous artists are honored, protected, and justly celebrated on the global stage.

Artist Ronnie Tjampitjimpa, Alice Springs, Northern Territory, 2007

As someone who's seen both the finance and art worlds up close, what are the parallels between a successful portfolio and a successful collection?

GP— In essence, while the underlying metrics differ, both a successful financial portfolio and a successful art collection are built on a foundation of disciplined research, strategic planning, patient long-term vision, and a clear understanding of risk, all underpinned by a purpose that extends beyond mere monetary accumulation. For art, that purpose is often deeply personal and culturally resonant.

My background in finance informed me and my approach towards the art market, emphasizing this disciplined research, long-term vision, and strategic growth. Over the years it became increasingly clear that "Art" was an alternative asset class, presented in such a way that it competed and fitted into a portfolio of assets, just as stocks and bonds do. A "bucket" with different liquidity considerations but an asset class all the same. Financial institutions indeed started to offer it as a "value added" service to help mitigate risk in the larger portfolio of wealthy clients. The core of my work at ReDot Fine Art Gallery is driven by a genuine passion for the art itself and a profound respect for the artists and their heritage but marrying this investment overlay.

We live in a post-COVID world now and the art market has certainly felt the impact of that. Your gallery operates on a hybrid model with a strong online presence and a handful of exhibitions per year. How did that decision come about and what does the "gallery of the future" look like to you now that more galleries are closing or downsizing?

GP— You're right, the art market felt the seismic shift of COVID-19. However, it purely accelerated trends that were already bubbling under the surface before this event and were inevitable and natural progression for the industry in the changing landscape of the modern new world. Galleries have had to adapt or become obsolete and close, forcing a serious rethink of their purpose and operations, using new modern technology.

After 20 years running a physical space, age and fatigue became a real issue, which has been recently highlighted very prominently by the closure of Blum and Venus of Manhattan. Running an art gallery is intense, all consuming. The move to a hybrid model was about optimizing our ability to connect, educate, and sell to our unique global audience, leveraging technology to amplify the reach and understanding of the incredible art we represent, well before the world was forced to embrace it by COVID-19. It was about expanding our cultural bridge and not "burning out."

I like to think my experience and background, and constant reflection, alerted me well ahead of the pandemic that the "gallery of the future" wasn't going to be a single, monolithic model.

The days of purely "brick-and-mortar" galleries are becoming rarer. The gallery of the future will almost certainly operate on a hybrid model, seamlessly blending physical and digital experiences, as the quality of digital resources improves.

a.) Elevated Online Presence: This isn't just a basic website. It means sophisticated virtual viewing rooms, high-resolution imagery, video tours, augmented reality (AR) features that allow collectors to "place" art in their homes, and compelling digital content like artist interviews and studio visits. Online platforms will be as crucial for discovery and initial engagement as they are for direct sales, especially for international clients.

b.) Strategic Physical Spaces: Physical galleries will become more experiential and focused. Instead of simply being retail showrooms, they'll serve as:

i. Immersive Exhibition Spaces: Hosting fewer, but more impactful, exhibitions that offer a unique sensory experience impossible to replicate online.

ii. Community Hubs: Organizing intimate events, artist talks, workshops, and gatherings that foster genuine connections between artists, collectors, and the wider public.

iii. Private Viewing Rooms: Offering exclusive, personalized consultations and viewings for serious collectors.

iv. Pop-up Locations & Collaborations: Experimenting with temporary spaces in unexpected locations or partnering with other businesses to reach new audiences.

In a crowded digital landscape, the "gallery of the future" will excel at authentic storytelling. It's not just about selling a piece of art; it's about sharing the narrative behind it, the artist's journey, and the cultural context.

Curatorial Excellence: Galleries will double down on their curatorial vision, presenting cohesive narratives that resonate with audiences and build a distinctive identity.

Transparency and Trust: Building trust through clear communication about provenance, pricing, and artist support, especially in a market where online transactions are increasing.

The pressure on smaller galleries, in particular, will lead to greater specialization and collaboration.

Niche Focus: Galleries might thrive by focusing on specific art movements, geographic regions (like Indigenous art), mediums, or emerging artists, allowing them to become authorities in their chosen field.

Strategic Partnerships: Collaborating with other galleries (even competitors), cultural institutions, art fairs, and even non-art related brands to share resources, expand reach, and create unique programming. This could mean shared exhibition spaces, joint marketing efforts, or co-hosting events.

While online sales were a quick fix during lockdowns, the future gallery will integrate technology in more sophisticated ways, using data to understand collector behavior, exhibition engagement, and market trends to inform strategic decisions. Ultimately, the "gallery of the future" will be more agile, digitally savy, and focused on building meaningful relationships and communities around art. It will recognize that while art can be discovered online, the human connection and visceral experience of encountering art in person remain irreplaceable.

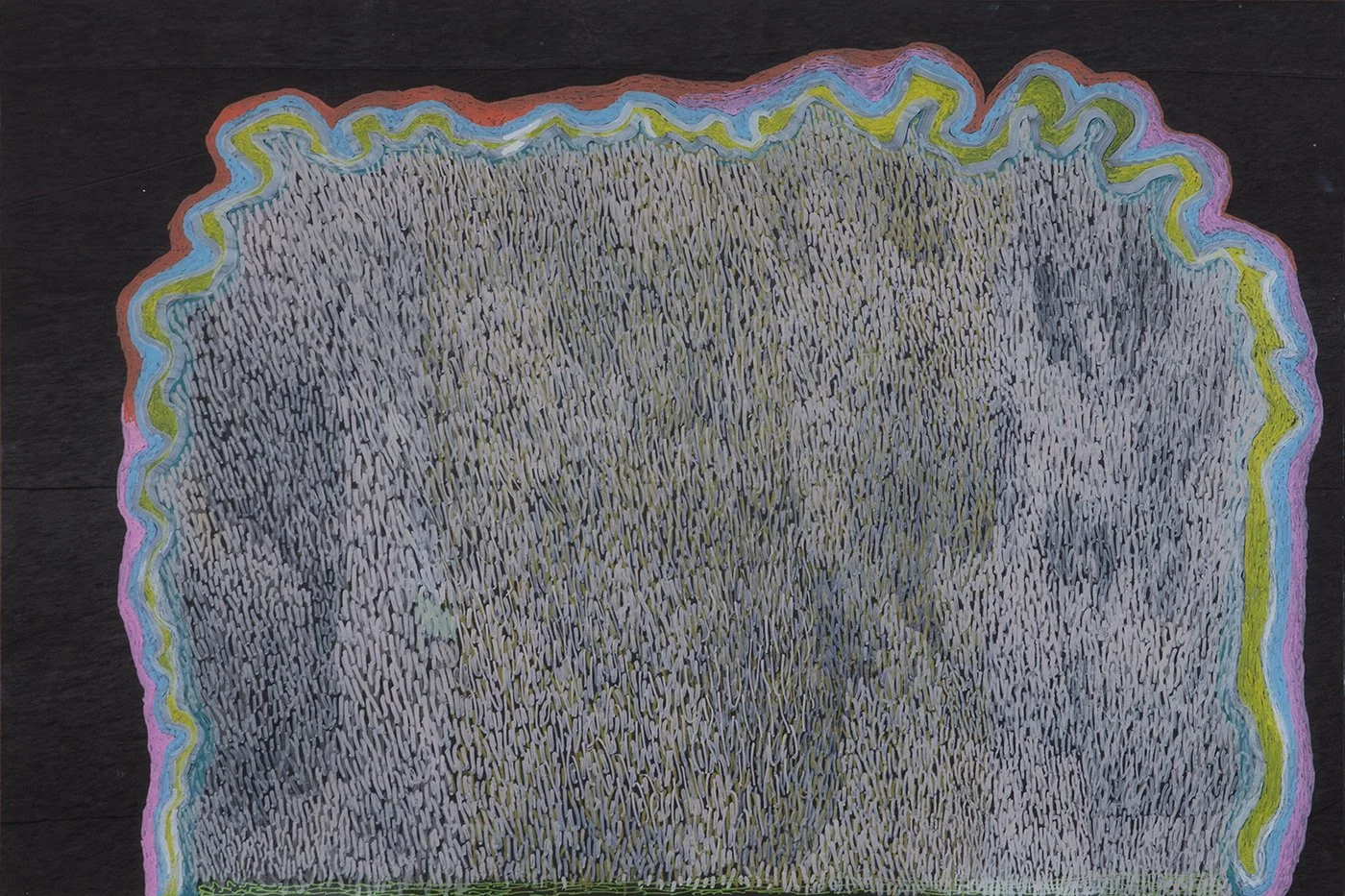

Artist Timo Hogan

How close can the digital truly come to replicating the physical experience of viewing and feeling art?

GP— This is a fantastic and complex question that gets to the heart of what art means to me. As someone who has spent significant time with physical artworks, especially those with deep textural and cultural layers like Australian Indigenous art, I believe the digital can come remarkably close to replicating some, if not all, aspects of the physical experience, but it currently cannot fully replace it. Advancements in virtual reality (VR) and 3D modeling allow for immersive walkthroughs of virtual galleries or even detailed 360-degree views of sculptures. You can "move" around the artwork, altering your perspective, which is a significant improvement over the past "flat images". Augmented reality (AR) apps can even place artworks virtually in your own space and its evolution is very exciting. So, how close can digital come? It can come very, very close in terms of information dissemination and initial visual exposure. It can be an incredible gateway to art, sparking interest and providing unparalleled educational resources, it can't yet replace fully the real experience but who knows how that will evolve over the coming years.

A physical gallery is a multi-sensory experience. The quiet hum of the space, the scent of the materials, the temperature, the sounds of other viewers, the architecture of the building itself - all contribute to the emotional and intellectual engagement with the art. Digital viewing is often a solitary, disembodied experience at the moment - though as I say evolving incredibly fast. You can see the illusion of texture digitally, but you cannot feel it. The tactile quality of paint, the grain of wood, the coolness of marble, the subtle undulations of canvas - these are crucial to experiencing art. For Australian Indigenous art, the texture of ochre, the raised dots, or the weave of a fibre sculpture are integral to its meaning and beauty.

There's a unique psychological and emotional connection that happens when you stand before an original artwork. Knowing it was touched by the artist's hand, that it exists uniquely in a physical space, contributes to a sense of awe and authenticity that a digital reproduction, no matter how perfect, struggles to convey right now. This is especially true for cultural objects like many Indigenous artworks, where their "being" is as important as their "looking." While online communities exist, the shared experience of viewing art in person, discussing it with fellow visitors, or interacting directly with a gallerist or artist at an opening, fosters a communal and social dimension that digital replicates imperfectly. So, for the full, immersive, and truly profound experience of art - especially for works where materiality, scale, and cultural context are paramount - the physical encounter remains irreplaceable (for now). The "gallery of the future" will therefore be a symbiotic blend where digital tools enhance accessibility and understanding, while physical spaces continue to provide the deep, multi-sensory, and emotionally resonant experiences that define our most profound connections with art.

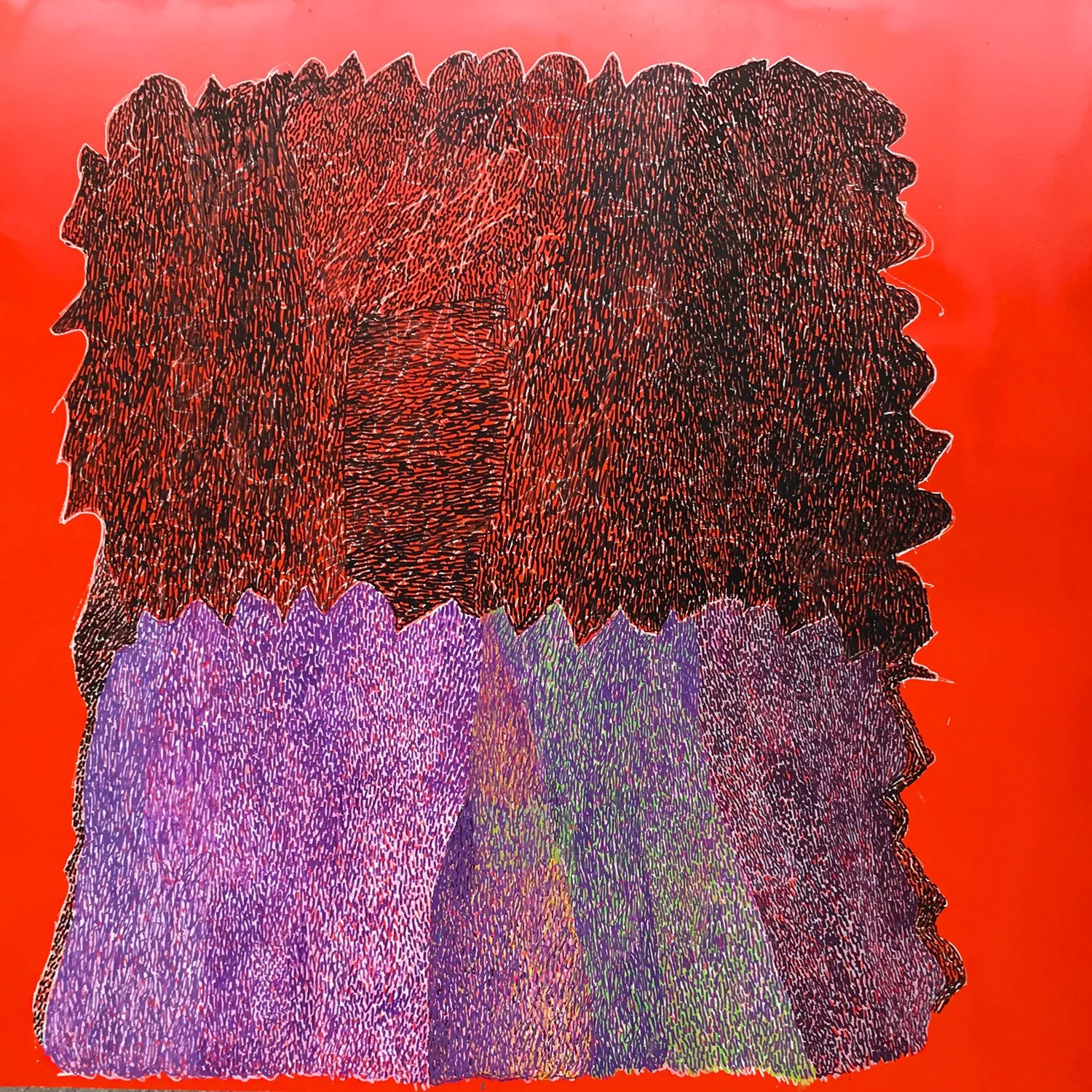

Artist Tommy May

If art is a form of diplomacy, what role do you believe Indigenous art plays in the global cultural conversation today?

GP— Australian Indigenous art serves as an invaluable cultural ambassador. For many outside Indigenous communities, these artworks offer the first, and sometimes only, window into ancient traditions, deep spiritual connections to land, complex social structures, and unique worldviews. Through their art, Indigenous artists share narratives that have been passed down for millennia, allowing global audiences to connect with diverse human experiences and understand the richness of cultures often marginalized or misunderstood. This direct engagement fosters empathy and breaks down stereotypes, moving beyond purely ethnographic or anthropological interpretations to acknowledge the artistic merit and contemporary relevance of these works. Indigenous art has fundamentally transformed the global art landscape. Its unique aesthetics, conceptual depth, and deep connection to place and ancestral knowledge have influenced contemporary art movements worldwide. Artists like Emily Kam Kngwarrey and Warlimpirringa Tjapaltjarri, to name but two, with their minimalist abstraction and profound spiritual underpinnings, have achieved international acclaim, prompting art critics and collectors to reconsider traditional Western art historical canons. This cross-cultural fertilization enriches the broader artistic conversation, proving that innovation and relevance can emerge from deeply rooted traditions.

Beyond cultural exchange, Indigenous art opens doors for dialogue on pressing global issues. Themes frequently explored in Indigenous art-such as environmental stewardship, sustainable living, intergenerational knowledge transfer, and resilience in the face of adversity, resonate deeply with contemporary challenges like climate change, social inequality, and cultural preservation we are facing today. When these artworks are exhibited internationally, they provide a platform for discussions on these shared concerns from unique, long-standing perspectives, offering alternative ways of understanding and interacting with the world.

In essence, Australian Indigenous art, as a form of diplomacy, doesn't just represent cultures; it actively shapes perceptions, demands recognition, and contributes vital perspectives to the ongoing global conversation about humanity's past, present, and future. It's a testament to enduring creativity, resilience, and profound wisdom.

When you think about ReDot's impact, not just as a business but as a cultural bridge connecting Indigenous artists to the global art market, what are you most proud of?

GP— What I'm most proud of is being part of a movement that not only celebrates extraordinary artistic talent but also champions cultural self-determination, reconciliation, and the powerful role of art in fostering a more understanding and respectful global community. The state of the current world leaves me saddened and hosting severe concerns for the future of humanity, I hope the gallery helps rebalance, even in a very small way, this imbalance. We started as the only dedicated gallery of its kind in Southeast Asia. I'm proud of how we've helped elevate the status of Australian Indigenous art from a niche "ethnical art" category to a respected and sought-after segment of the global contemporary art market. We've shown that its artistic merit stands alongside any other great art tradition.

The trust and reputation we've built over the years, both with the art centers in Australia and with collectors worldwide, is a source of immense pride. This reputation is built on consistency, integrity, and a deep, genuine passion for "the art" and the people who create it. By providing a platform for this art, we indirectly support the intergenerational transfer of knowledge. Artists are empowered to continue their practice, mentor younger generations, and ensure that ancient stories and languages remain alive. This contribution to cultural continuity is perhaps the most profound impact of all. Knowing that our work directly contributes to the economic sustainability of remote Indigenous communities is incredibly fulfilling. The income generated through art sales supports essential services, cultural programs, and helps maintain vibrant community life on Country. It's a tangible way we see our efforts making a real difference.

For more information on ReDot Fine Art Gallery, please visit here.

Images courtesy of Giorgio Pilla.